Dietary fats are a topic that causes confusion for many people, and saturated fat is perhaps the most controversial.

This article cuts through the noise to explain precisely what saturated fat is, how it behaves in the body, and what scientific research tells us about saturated fat consumption.

Let’s take a look at everything you need to know.

Table of contents

What Is Saturated Fat?

First of all, let’s define what saturated fat is.

All fatty acids are composed of carbon atoms bonded to hydrogen atoms. In the case of saturated fat, the carbon atoms are fully surrounded—or “saturated”—with hydrogen atoms.

However, there are some differences between saturated fatty acids and other types of fat.

Saturated Fat Structure

Each carbon atom can use a maximum of four bonds to connect to other atoms.

Here is a simplified illustration showing the structure of a saturated fatty acid:

As you can see, the saturated fat structure has single bonds connecting each carbon atom (C-C-C-C-C) and two single bonds connecting each carbon atom to two hydrogen (H) atoms.

However, unsaturated fats contain double bonds between carbon atoms, meaning that they will be missing one bond to a hydrogen atom.

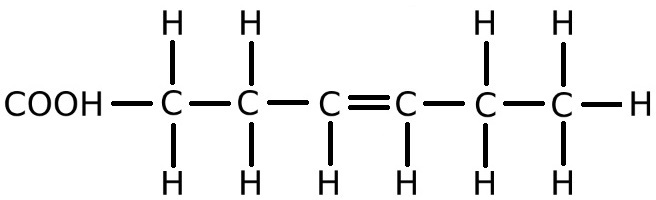

For example, here is another simplified illustration showing the monounsaturated fat structure:

Did you spot the difference? There is one carbon-carbon double bond in the middle, so those two carbon atoms are missing a bond to a hydrogen atom. Since the carbon atoms are not fully saturated with hydrogen, this is called a monounsaturated (one double bond) fat.

Another type of fat—polyunsaturated fat—contains multiple double bonds.

Saturated Fatty Acids

There are many different types of saturated fat, and each has a different structure and carbon-chain length.

Each saturated fatty acid belongs to a specific classification depending on its carbon-chain length—how many carbon atoms it contains.

These classifications can be described as:

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): Five carbon atoms or fewer

- Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs): Six to twelve carbon atoms

- Long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs): Thirteen to twenty-two carbon atoms

Here are some of the most common saturated fatty acids we can find in food:

| Saturated fatty acid | Chain length | Most significant food sources |

|---|---|---|

| Butyric acid | C4 (SCFA) | Butter, dairy |

| Caproic acid | C6 (MCFA) | Dairy, coconut |

| Caprylic acid | C8 (MCFA) | Coconut, dairy, palm kernel oil |

| Capric acid | C10 (MCFA) | Coconut, dairy, palm kernel oil |

| Lauric acid | C12 (MCFA) | Coconut, dairy |

| Myristic acid | C14 (LCFA) | Coconut, palm kernel oil |

| Palmitic acid | C16 (LCFA) | Abundant in many animal and plant fats |

| Stearic acid | C18 (LCFA) | Animal fats, cocoa butter |

Saturated Fat Can Raise LDL Cholesterol (LDL-C)

Public health guidance advises limiting saturated fat intake.

This is because diets high in saturated fat can lead to elevations in LDL cholesterol—also known as LDL-C (1, 2, 3). You may have heard LDL-C referred to as “bad cholesterol” in the media.

Multiple large studies consistently find a strong link between elevated LDL-C levels and a higher risk of both cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular death (4, 5, 6, 7).

Unlike omega-3 and omega-6, saturated fats are nonessential because the body can make them from excess carbohydrates and certain amino acids. This process is called de novo lipogenesis.

LDL Particle Size (and Does It Matter?)

LDL-C particles come in various sizes, from “large and buoyant” to “small and dense.” Saturated fat tends to increase large LDL particles, which are considered less of a risk for cardiovascular disease than smaller particles (8).

It is thought that smaller particles are more likely to penetrate artery walls.

Importantly, while some LDL particles are more atherogenic (plaque-forming) than others, higher levels of all LDL particles increase cardiovascular risk.

Large review studies show that although smaller LDL particles may more significantly raise cardiovascular disease risk, total LDL particle number matters most, with higher particle numbers consistently associated with increased risk (9, 10).

Not All Saturated Fatty Acids Have the Same Effect

Not all saturated fatty acids have the same impact on LDL-C levels. Some are more potent than others, with palmitic, lauric, and myristic acids raising LDL-C most significantly (11, 12).

In contrast, stearic acid has a minimal effect on LDL-C levels, partly because it is partially converted to oleic acid—a monounsaturated fat—in the body (13, 14).

That said, most food sources of saturated fat tend to contain multiple saturated fatty acids, and overall saturated fat intake does tend to increase LDL-C.

The Polyunsaturated-to-Saturated Fat Ratio

As well as the absolute amount of saturated fat in the diet, the ratio of dietary polyunsaturated to saturated fat intake impacts LDL cholesterol levels (15).

Research by Ancel Keys et al. in 1957—known as the ‘Keys Equation’—demonstrated that polyunsaturated fats, particularly omega-6, lower LDL-C, whereas saturated fat raises it. The Keys Equation predicts that saturated fat increases cholesterol about twice as much as polyunsaturated fat lowers it, per gram (16).

Since then, studies have confirmed that a higher omega-6 to saturated fat ratio reliably decreases LDL-C. The 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee discussed this evidence before the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans were published (17).

A 2020 systematic review by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee concluded that strong evidence shows replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats lowers heart disease risk and cardiovascular mortality (18).

In an advisory statement, the American Heart Association (AHA) states that lowering saturated fat intake while increasing polyunsaturated fats will reduce cardiovascular disease rates (19).

Additionally, a 2017 systematic review found that replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat lowers heart disease events and total mortality (20).

Which Foods Contain the Most Saturated Fat?

Some foods contain far more saturated fat than others.

For example, animal fats, fatty meats, coconut and palm oil, pastries, cakes, cookies, and ice cream tend to have the highest levels.

Additionally, any foods made or fried with butter or palm oil are likely to contain significant saturated fat.

Current Recommendations For Saturated Fat Intake

Let’s now review current recommendations on saturated fat consumption from major public health organizations.

The 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines For Americans (DGAs)

The 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) advise keeping saturated fat intake at less than 10% of daily calories (21).

On a 2,000 calorie diet, this translates to less than 20 grams of saturated fat per day. As dietary fat contains 9 calories per gram, 20 grams (180 calories) is within 10% of daily calories on a 2,000 calorie diet.

Using precise figures, here’s what 10% of daily calories from saturated fat looks like at various calorie intakes:

- 1200 calories: 13 grams of saturated fat

- 1500 calories: 16 grams of saturated fat

- 1800 calories: 20 grams of saturated fat

- 2100 calories: 23 grams of saturated fat

- 2400 calories: 26 grams of saturated fat

- 2700 calories: 30 grams of saturated fat

- 3000 calories: 33 grams of saturated fat

- 3300 calories: 36 grams of saturated fat

- 3600 calories: 40 grams of saturated fat

- 3900 calories: 43 grams of saturated fat

The American Heart Association (AHA)

The AHA advise limiting saturated fat more strongly.

They recommend a diet containing where saturated fat is less than 6% of daily calories (22).

The National Institutes of Health (NIH)

NIH guidance advises limiting saturated fat intake to less than 10% of total daily calories (23).

The World Health Organization (WHO)

Likewise, the WHO also recommend keeping saturated fat intake below 10% of daily calories (24).

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

The EFSA doesn’t set a specific limit, but they do recommend keeping saturated fat intake low.

They advise that—within the context of a nutritionally adequate diet—saturated fat should be “as low as possible” (25, 26).

Is Saturated Fat Bad For You?

It is important to note that guidance on “limiting” saturated fat means reducing intake—it does not mean avoiding it.

Numerous foods that contain saturated fat that are linked to health benefits.

For example, foods such as oily fish and yogurt are consistently linked with health benefits:

- Yogurt: A large 2022 review study involving 896,871 participants found high intake of yogurt (compared to low) was significantly associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk and overall mortality (27).

- Oily fish: A 2022 systematic review strongly linked fatty fish consumption with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality (28).

In other words, consider the food source rather than just its saturated fat content.

Yogurt and oily fish are quite different from consuming large amounts of butter and palm-oil-rich baked goods.

Summary

In summary, high saturated fat intake raises LDL-C, and elevated LDL-C is strongly linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Most health bodies recommend limiting saturated fat intake to less than 10% of total calories.

However, nutrient-rich foods containing saturated fat—like yogurt and seafood—can still play a role in a healthy overall dietary pattern.

For more on dietary fat, see this guide to omega-3.